Being sustainability-minded typically comes with an orientation toward thinking about the future. After all, one of the ultimate goals of sustainability is to leave the planet better than one found it as a loving act toward future generations.

So what role does history, specifically, Black history play in this?

A significant role.

In order to fully understand where the movement toward a just environment for all is going, we need to examine where it has been, what struggles have been faced, and what lessons this offers for present-day challenges. One complexity of commemorations like Black History Month is the potential for some to think of racial injustice as an object of the past, viewing injustices exclusively as historical items and making it difficult to see how they continue to impact lives in the present day. In order to prevent this illusion, our commemorations of the past are best served with a sense of how past legacies can be further built upon.

The intensification of climate change makes our environmental-crisis a very immediate, present-day reality, coupled with uncertainty about the future. In order to respond with appropriate urgency, we need to quickly invest and scale up a variety of solutions. The good news is that these solutions are available, and many have been around for decades thanks to the contributions of Black pioneers in fields like agriculture, science, and civic engineering.

From W.E.B. Dubois’ studies on how discrimination impacted isolated Black communities, to Harriet Tubman’s intimate knowledge of forestry, land navigation, and bird calls equipping her with the skills needed to lead enslaved people away from captivity, stewardship of the land has long been intertwined with Black history. At the same time, the history of enslavement and forced labor in the United States also adds a level of complexity when it comes to the story of land. Here are a few of the ways some of these Black legacies are directly connected to some of the most important solutions and high-stakes topics as we face our current climate crisis.

Equipping Rural Farmers

Prior to the Great Depression, a number of successful Black farming communities could be found across the rural South. Nearly one million Black farm operators were recorded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), more than at any other point in U.S. history. Communities like Mound Bayou, Mississippi, connected Black-owned businesses to local farms.

The success of these communities came from efforts to provide rural farmers with the knowledge needed to succeed. T.M. Campbell, a field agent for the USDA was the lead Farm Demonstration Agent in Macon County, Alabama, which gave him the opportunity to oversee rural development across the South. Among his many accomplishments was the establishment of a rural extension program designed to promote healthy farming practices to Black farmers. These included spreading information on farm-grown foods and promoting crop diversification. Campbell’s rural extension placed an emphasis on self-sufficiency and crop diversification as a means to reduce dependency on cotton.

The U.S. has seen several drastic shifts in its population since this time. The Black population in urban areas is nearly double that of rural areas, and this can be largely attributed to elements of the New Deal that displaced many Black farmers by reducing the size of farmland in an effort to lower crop prices. A century of discriminatory practices have resulted in a diminished number of Black farmers, fewer subsidies, and greater debt.

As the climate crisis becomes more widely felt across the globe, it’s important to note that rural populations will be the first to feel its effects. Nearly nine in ten people living in poverty around the world are in rural areas. Climate change affects their ability to grow sufficient food for their own nutrition or their livelihood. Practices promoted by T.M. Campbell that were widely adopted in Black farming communities are also widely beneficial to global communities most threatened by climate change. Crop diversification and self-sufficiency are widely promoted in Plant With Purpose’s farmer field schools across rural communities around the globe. These build a greater resilience against the uncertainty of climate change.

Preserving Soil Health

Soil health is commanding greater attention from environmental actors. The quality of an area’s soil is a central component of regenerative agriculture, one of Plant With Purpose’s most important practices. Building soil health not only helps rural communities grow better food more efficiently, but it also helps to mitigate climate change by sequestering greenhouse gases beneath the earth.

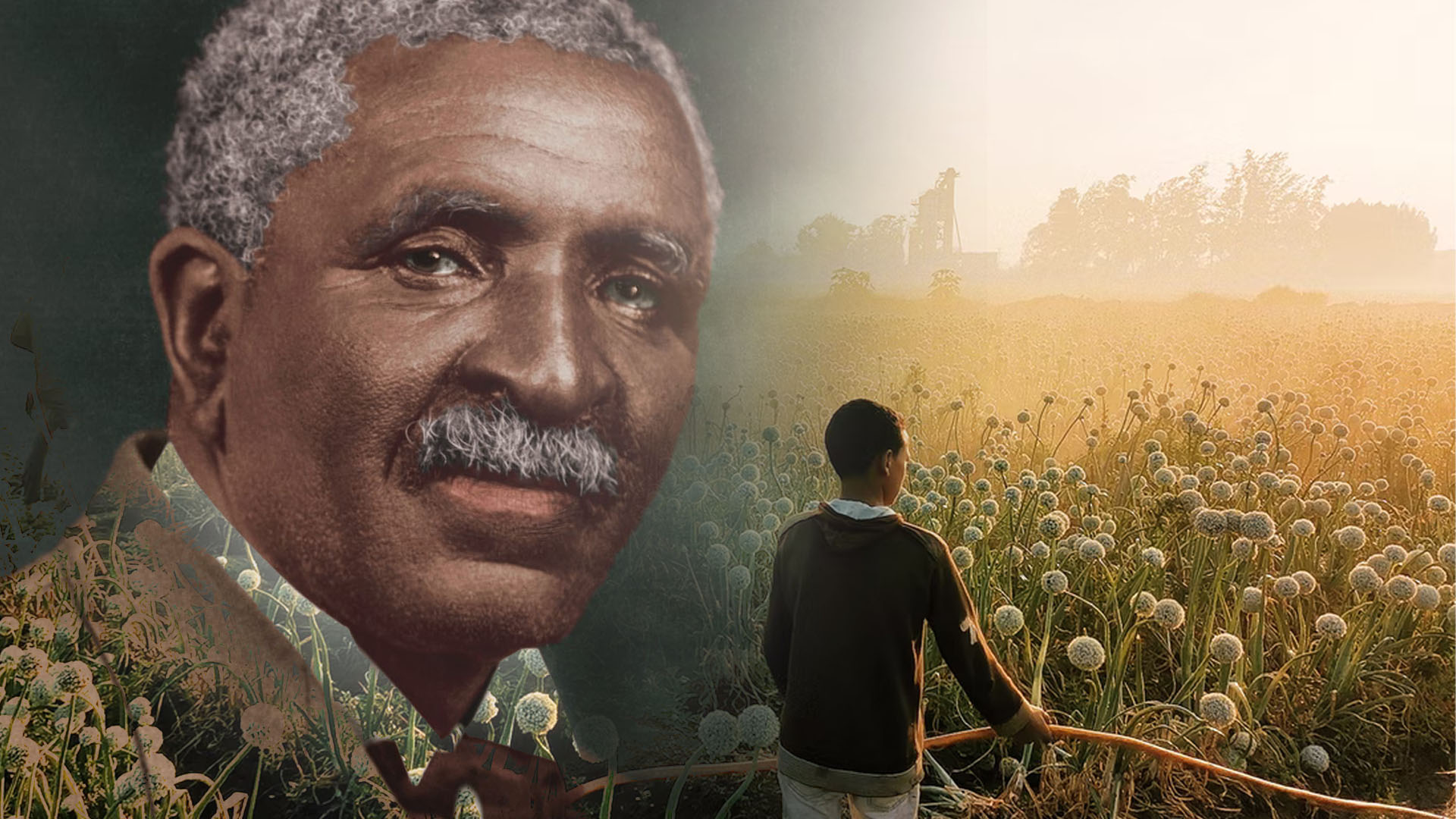

Black history provides lot of what we know about the importance of soil in an ecosystem can be attributed to one of the most prolific Black scientists in U.S. history: George Washington Carver. While many recognize Carver for his work and research with peanuts, that only scratches the surface of his vital contributions to our knowledge of sustainable agriculture. Dr. Carver emphasized the value of using compost to maintain the presence of nutrients and organic matter within soil, essentially the central idea behind regenerative agriculture. He began promoting the peanut as a versatile rotational crop that could help restore the soil of the South that had been depleted of its nitrogen by cotton.

Awareness of soil as a carbon sink and climate solution has taken off recently. Documentaries like Kiss the Ground have highlighted the importance of conserving soil through regenerative agriculture. In Plant With Purpose’s programs, we have seen the widespread healing effect of soil restoration on rural communities. Regenerative practices, much like those pioneered by George Washington Carver, help rural communities devastated by soil erosion recover their ability to grow food, preserve the water cycle, and protect biodiversity. Similar to the way rotational cropping helped the South recover from cotton’s harmful impacts, regenerative agriculture can help restore ecological health to places that have been damaged by harmful farming practices like monocropping or chemical usage.

Community Supported Agriculture

Awareness continues to grow toward all the ways globalized industrial agriculture harms the environment. The toxic effects of incentivizing farmers to heavily invest in just one type of crop, like through soybean subsidies in the U.S., that allow the product to be shipped around the globe to be sold at the lowest price possible seem obvious. From the pollution of transport and chemical fertilizers, to the vulnerability to disease created by growing a single crop, to the economic injustice of paying as little for human labor as possible, many are looking for alternatives when it comes to their food.

This awareness has raised interest in local food and in minimizing the distance between food growers and customers. Farmers markets, locally grown labeling systems, and local farm subscription boxes have all made this incrementally easier.

Many of these ideas, however, were popularized by a Black agricultural professor from Alabama, Booker T. Whatley. Dr. Whatley wrote and taught extensively about a direct marketing regenerative farming system. In addition to the traditional regenerative farming practices, he introduced the idea of attaching them to a more cooperative marketing framework. One of his most popular concepts was the Pick-Your-Own farm, which remains extremely popular. Establishing subscription services and collaborations between local businesses and nearby farms through a buyers’ club helped ensure the financial viability of sustainable farming. Today, they offer a vision for what an alternative food system could look like, beyond the unsustainable one that has dominated our planet for so long.

Food Justice for Black Farmers

Food justice for Black communities has long been a driving force for equity, and it continues to be an important area of concern. One of the boldest voices throughout the Civil Rights Movement to secure rights for Black voters came from Fannie Lou Hamer, an activist who used food as a means to protest systemic oppression.

Hamer’s establishment of a Freedom Farm Cooperative helped provide Black Americans with a pathway to opportunity and nutrition from which they had been systemically excluded. As the USDA routinely rejected applications for land loans, denied subsidies available to white farmers, and imposed other policies making farming more difficult for Black agriculturalists, many resorted to sharecropping for survival. Hamer’s cooperative created access to affordable housing, enriched the nutrition of Black communities, and enhanced entrepreneurship opportunities. This intermixing of social solidarity, nutrition, entrepreneurship, and farming are similar to the areas of overlap seen in our international development work.

Hamer’s work is carried on today by activist farmers like Leah Penniman of Soul Fire Farms who combats racism through food. While the U.S. once had nearly a million Black-owned farms, around 80% of this farmland has been lost, also accounting for billions of dollars in lost revenue. This dynamic is also seen globally. Loss of land, cultural knowledge around farming, and soil and ecological health, all keep environmental justice at bay. It is a reminder that the struggle for justice has often taken place on the farm.

As we celebrate Black history and the contribution of numerous Black legacies toward a sustainable future, let’s remember that the struggle for a just world and a healthy planet is ongoing. Knowing history gives us focus in the present, so we can together build a just and sustainable future.